In continuation of the myth-busting stylings of Physics Today‘s The Copernican myths I thought to post a similar treatment of the issues relating to Galileo Galilei from Philip J. Sampson’s truly excellent book 6 Modern Myths About Christianity and Western Civilization beginning on p. 27. Philip Sampson is a mediator, family court advisor and research fellow. He holds a Ph.D. in social sciences from the University of Southampton in England.

While there are no images in the book, I thought to place some within this post. Following are selections from the text:

…

The modem period began, claims [Bertrand] Russell, with the Renaissance, which started to free men’s minds from superstition and religion, and established reason as the foundation for science. This new freedom, however, was opposed root and branch by the church, culminating in the clash between religion and science symbolized by Galileo.

Bertrand Russell

…

Galileo: The Received Version

Like any story, that of Galileo has a plot, characters, a setting and props. The plot is the war between religion and science, and it is presented to us not with facts but through the adventures of a charismatic individual. Armed only with a telescope and reason, plucky Galileo stood against the might of the church. He was tortured by the Inquisition, condemned as a heretic, and wasted away in a prison cell; Italian science floundered. The main drawback to this plot is that most of it is untrue.

…

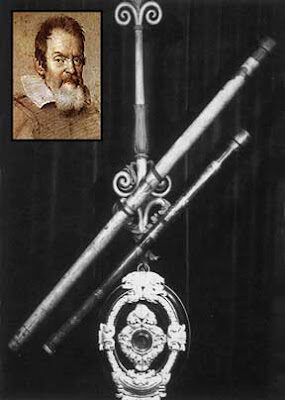

As Bertrand Russell says, “everyone knows”1 about Galileo. Scientist and hero, he invented the telescope, discovered how the earth moves around the sun, conducted his famous experiment on the (even then) Leaning Tower of Pisa and courageously added to his recantation of the earth’s motion: “Eppure si muove” (“yet it does move”). As it happens, little of this is true either. However, where decisive scientific discoveries are lacking, the myth supplies them: the Leaning Tower and the telescope build up Galileo’s character nicely.

Galileo Galilei

…

The Wrong Man

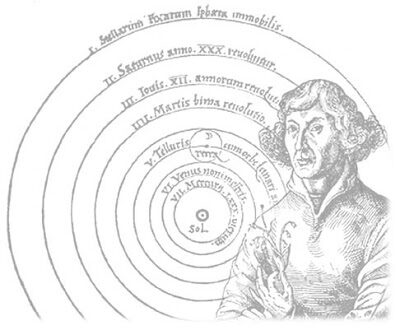

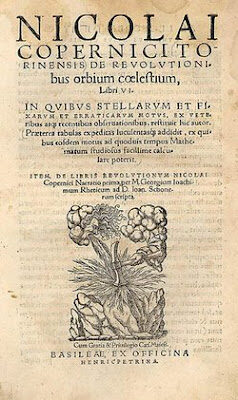

There is a puzzle here, however. Why Galileo? At first blush, the prime candidate for the hero of the Copernican Revolution must surely be Nicolaus Copernicus. Yet most versions of the story turn not on the retiring Canon Copernicus but on the name of Galileo Galilei, a man born some twenty years after Copernicus died. For Copernicus could not carry the plot forward. He was, after all, a canon of the Church and enjoyed the support of the cardinal of Capua and Pope Paul III. His book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, published in 1543, circulated at little or no cost for some seventy years. Galileo is therefore much more congenial to the storytellers, for even though he received Church pensions, he was at least condemned by the Holy Office in 1633 for teaching that the sun is the center of the universe and that the earth moves around it.

Nicolaus Copernicus

…

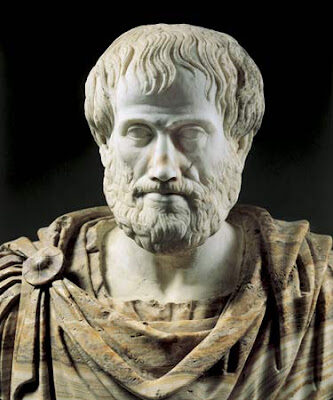

Scholarly CirclesFrom the late Middle Ages the dominant model of the universe in western Europe was derived from Aristotle, who reasoned that the heavens, the perfect and immutable realm, would also be unchangeable in its physical qualities and motions.

Aristotle’s physics is complex and differs greatly from what is now taught as science in our schools, but it would be a great mistake to suppose that it was therefore foolish or self-evidently wrong. I can give only the briefest outline here, but the reader must remember that the majority of early-seventeenth-century astronomers were Aristotelians for reasons defended in logic and observation.

Aristotle

…

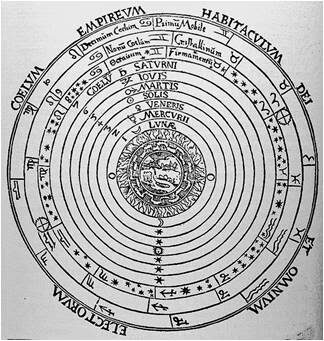

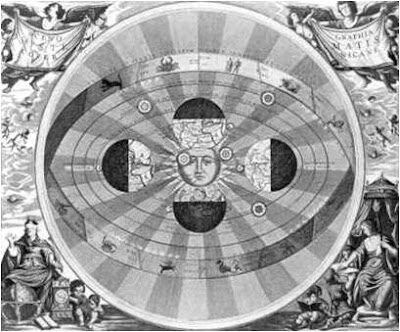

Ptolemy’s universe. In the second century A.D., Ptolemy constructed an astronomical system based on Aristotle’s ideas

Ptolemy

…

Ptolemy also considered alternative models, including the Pythagorean view that the earth rotates. However, he rejected this for a number of empirical reasons

…

By the early seventeenth century, numerous problems had accumulated with Ptolemy’s Aristotelian cosmology. Not only was Aristotelian physics increasingly criticized, but improved observations led to greater and greater complexity in the model. To try to resolve these difficulties Copernicus adopted the ancient Pythagorean hypothesis that the sun, not the earth, is at the center of the universe. This was not altogether successful, and Copernicus’s final model of the heavens was ultimately more complex than Ptolemy’s. It did, however, allow Copernicus to fix the order of the planets, perhaps his greatest achievement. In other respects Copernicus remained faithful to Aristotle, retaining the circular orbits as well as most of the Ptolemaic devices.

Galileo was a firm disciple of Copernicus, both in placing the sun at the center of the universe and in his otherwise conservative picture of the universe.

Pythagoras

…

The science writer James Newman…

It will never be known when man first became convinced that he was of cosmic importance, but the date this pretension was disposed of is pretty clear. The De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium of Nicolaus Copernicus was published in 1543….Nestled in the mathematics…was a concept that put man, in his place in the cosmos, as Darwin’s concept was to put him in his place on earth….Looking backward in history, it is easy for us to see that a moving earth and sun-centred universe gravely subverted Christian theology. If man’s abode was not at the centre of things, how could he be king.2

Although this is a common subplot of the Galileo story, it is mistaken. There is indeed a connection between the earth’s physical “position” in the universe and its status, but not the one often assumed. Aristotle emphasized the corruption of the earth in comparison with everything above the lunar sphere (remember the moon is the first of many spheres revolving around the earth). Indeed, in Aristotelian thought the earth was so far inferior to the heavens that the latter were believed to consist of a higher, finer substance-the fifth element, the quintessence. The earth was at the center not because of its significance but because it is everywhere below the heavens. Thus the pre-Copernican cosmology that the earth lies at the center of the universe is no compliment to earth’s occupants.

The center is the lowest place in the universe, not the most important. The hierarchy of perfection stretches up beyond us in concentric circles, rank upon rank. Thus the fourteenth-century Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, in The Divine Comedy, locates the pit of hell centrally in the “great fundaments of the universe, on which all weights downweigh.”3 The heavens, by contrast, were everywhere lifted up above the earth, incorruptible and divine.

The Copernican system, far from demoting man, destroyed Aristotle’s vision of the earth as a kind of cosmic sink, and if it did anything, it elevated humanity. In making the earth a planet, a heavenly body, Copernicus infinitely ennobled its status. Galileo exploited this changed status of the earth when he had his mouthpiece, Salviati, say: “We seek to ennoble and perfect [the earth] when we strive to make it like the celestial bodies, and, as it were, place it in heaven, from which your philosophers [namely, Aristotle] have banished it.”4 As for size, it matters, but not as is often supposed.

As we have seen, if overturning Aristotle’s vision of the place of the earth is to have any metaphorical meaning at all, it elevates humanity to the status of heavenly creatures. In this sense the Enlightenment was indeed a Copernican Revolution.For it made man the source and origin, as well as the measure, of all things. It placed him at the center of creation in a far more radical sense than that wrongly ascribed to pre-Copernican astronomy and the church.

Man became his own god, or at least his reason did. As Charles Darwin put it, man’s “god-like intellect…has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system.”5 Indeed, as the astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle has pointed out, Darwinism similarly elevates mankind, for the neo-Darwinist picture of evolution relies on the predilection, fueled by “anti-religion,” to see everything as centered on the earth.6 Darwin’s theory of evolution placed man at the very apex of nature, where a less geocentric point of view would take into account the constant interaction between the earth and the universe as a whole.

Charles Darwin

…

A Victim of Spin?

It has been said of Galileo that his fame rests on discoveries he never made and feats he never performed.

…

Galileo’s major contributions to astronomy were the observations made before 1613, namely, the existence of sunspots, the irregularity of the moon’s surface, the phases of Venus and the moons of Jupiter. It is not obvious how this proves “that the earth moves around the sun,” and for a very good reason: it doesn’t. Nor could it. Neither Galileo nor anybody else in the seventeenth century supposed otherwise.Galileo’s observations were important for another related reason: they conflicted with Aristotelian reason, for they indicated a lack of perfection in the heavens-the sun had “spots” and the moon blemishes. Moreover, his observations of Venus and Jupiter implied that the earth is not the center of all astronomical motion (although they do not imply that the sun is). Both of these conclusions are fatal to Aristotelian reasoning and therefore to Ptolemy’s cosmology.

Before publishing his conclusions in Letters on Sunspots in 1613, Galileo took the precaution of checking that the incorruptibility of the heavens was an Aristotelian belief and not a Church doctrine. Indeed, the Church largely accepted his conclusions, although the die-hard Aristotelians in the universities did not.

Ptolemaic Universe

…

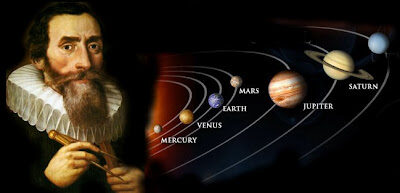

Galileo and the Church

Galileo delayed publishing his Copernican opinions for many years. He was nearly fifty when he first did so and approaching seventy at the time of his trial. Copernicus, also, had been reticent to publish. This hesitation is often attributed to fear of “the punishments of the Church.” We are told that when Copernicus did finally publish in 1543, his fears were realized as “the Inquisition condemned it as heretical.”7 The truth is more prosaic. Copernicus feared ridicule by his fellow astronomers. In the dedication of his book to Pope Paul III he wrote of his fear that he would be “hooted off the stage” and admitted that “the scorn which I had to fear on account of the newness and absurdity of my opinion almost drove me to abandon a work already undertaken.”8 His views were, indeed, rejected by the Aristotelian astronomers, but his book circulated for seventy years without condemnation by the Church. Galileo feared the same fate and was afraid of looking stupid. As he wrote in a letter to his fellow astronomer Johannes Kepler on August 4, 1597, he was “frightened by the fate of Copernicus himself…who…is…to an infinite multitude…(for such is the number of fools) an object of ridicule and derision.” The “fools” in question were not Inquisitors but his fellow astronomers, especially the Aristotelians in the universities.

Johannes Kepler

…

Galileo was first and foremost opposing Aristotle, not the Bible, and for the majority of early-seventeenth-century astronomers, this put him on the fringes of “science”; his was not a cutting-edge theory but an ancient Pythagorean view that had been discredited by Aristotle.

…

Far from being constantly harried by obscurantist priests, he was feted by cardinals, received by Pope Paul V and befriended by the future Pope Urban VIII who, in 1620, wrote an ode in his honor. The historian Georgio de Santillana observed in 1958 that flit has been known for a long time that a major part of the Church intellectuals were on the side of Galileo, while the clearest opposition to him came from secular circles.”9

Galileo Galilei

…

Freedom of speech. The Church’s response to Galileo is often put down to “a fear of discussion and debate,”10 but that is not so. Alternative astronomical hypotheses were freely discussed, including Copernicus’s astronomy, which, as Bellarmine remarked (in a letter to Paolo Foscarini, April 12, 1615), made “excellent good sense” as a hypothesis.

…

The book that led to Galileo’s trial was his 1632 treatise Dialogue Concerning the Chief World Systems. This took the form of a debate between protagonists, each representing a different view. The Aristotelian opponent of heliocentrism was called Simplicio… In other words, he concluded his treatise by effectively calling the very Pope [Pope Urban VIII] who had befriended him a simpleton for not agreeing with Galileo. This was not a wise move, and the rest is history. Galileo himself was convinced that the “major cause” of his troubles was the charge that he had made “fun of his Holiness” rather than the matter of the earth moving.11

He was certainly detained and was forced to abjure heliocentricism, but, as befitted his status, he was given his own rooms and servants. Moreover, he did not die a broken, lonely man in exile. He returned to his own home with his pensions from the Church intact. He could not travel freely, but he continued to write and receive visitors.

…

Galileo was interrogated by the Holy Office in April 1633. Modem scholarship has long rejected the simplistic myth, which has grown since the Enlightenment, of “a clash between enlightened reason in the form of Galileo and oppressive reaction in the form of the Church.”12 Galileo scholar Maurice Finocchiaro takes it for granted that the events of 1633 involve complex intrigues of politics and patronage rather than “dogmatic reservations of the Church” about biblical teaching.13 As the historian William Shea puts it: “Galileo’s condemnation was the result of the complex interplay of untoward political circumstances, political ambitions, and wounded prides.”14

Indeed, Galileo’s rhetoric, his position as a court favorite and even contemporary eucharistic disputes have all been considered factors in his downfall.15 But the received version of the Galileo story focuses exclusively on the supposed conflict between Galileo’s science and the teaching of the Bible, so we will turn to that next.

Pope Urban VIII

…

[Bertrand Russell wrote]

[John] Calvin…demolished Copernicus with the text: “the world also is established, that it cannot be moved” (Ps 93:1),and exclaimed:”Who will venture to place the authority of Copernicus above that of the Holy Spirit?” Protestant clergy were at least as bigoted as Catholic ecclesiastics…[but] had less power.16

…

Andrew White, a keen advocate of the received story of Galileo and the probable source of the misquotation of Calvin, claimed that this “accommodation theory” of Scripture is a late invention aimed at rationalizing a nonliteral reading of the Bible in the light of scientific discoveries. But this is not so. Calvin, Kepler and Galileo held such views, as did Newton. In fact, they have an ancient and continuous history. In the fourth century Augustine…In the thirteenth, Aquinas…in the mid-fourteenth century Nicholas Oresme…Galileo himself quoted Cardinal Baronius’s maxim that the “Holy Ghost intended to teach us how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go.”17

Copernican System

…

In fact, there is a strong school of thought that detects not warfare between science and religion but direct connections between them. Far from trying to resist science, the Reformation replaced Aristotelian and Neo-Platonic reasoning with insights from the Bible and thus provided the soil that enabled science to grow.

…

Space prevents a detailed discussion of the relationship between religion and the rise of science,18 but I will briefly mention four aspects: the de-deification of creation permitting experiment without impiety; the biblical task of dominion that facilitated the growth of technology; the recognition of reason as within creation and not over it; and trust in God’s covenantal faithfulness that suggests that it is worthwhile seeking laws governing the world.

Philip Sampson goes on to discuss these points under the headings of: “Nature created, not divine,” “Dominion not domination,” “Reason set free” and “Covenant Law.”

6 Modern Myths About Christianity and Western Civilization is a very, very informative book while being very, very readable and captivating. Philip Sampson likewise deals with the following topics in his book: Darwin – A Story of Origins, The Environment – A Story of Mastery, The Missionaries – A Story of Oppression, The Human Body – A Story of Repression, Witches – A Story of Persecution. He also introduces the concept of “stories and myths” and concludes with “Modern Myths in a Postmodern World.”