Hereinafter, we will consider occurrences at the Greer-Heard Forum of 2008 AD.

The forum’s topic was the reliability of New Testament manuscripts as pointers to the original text.

The lectures and discussions primarily featured Dan Wallace (Dallas Theological Seminary) and Bart Ehrman (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) with contributions by Michael Holmes (Bethel University), Dale Martin (Yale University), David Parker (Birmingham University) and William Warren (New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary).

I will be gleaning from the reports of the forum written by Ed Komoszewski from the theology blog Parchment and Pen; part 1 and part 2.

Let us begin by one of the most interesting and telling exchanges which, interestingly enough, took place during the Q&A between Joe Schmo and Bart Ehrman (Gentiles understand that “John Schmo” is the Jewish equivalent of “John Doe,” right?):

a questioner asked Ehrman about his text-critical method, noting that Ehrman seemed to always find the least orthodox readings and argue that they were the original readings. What Ehrman said was, frankly, unbelievable. He basically said that he would find the reading that he liked, and then find the evidence to support it! This sure sounded as though he was starting from his conclusions rather than beginning with a question.

Not surprisingly, some folks audibly gasped at this response.

In my essay Bart Ehrman, Interrupted – on the Bible and Christianity I noted that Ehrman does not reject the Bible, its God and Christianity due to the Bible problem but based on his emotions—as he, himself admits very openly. Now we see how his emotionally driven rebellion against God is the very premise upon which he builds his scholarship.

Interestingly:

[Dale] Martin, who is one of Ehrman’s good friends (a point whose significance will soon be seen), was the only non-textual critic on the panel. He gave perhaps the liveliest lecture of the bunch. Although he was supposed to argue on behalf of Ehrman, he essentially ripped him for not having a theology of scripture, for leaving the faith with insufficient evidence to do so, and for ignoring interpretation and tradition too much. He especially picked on Ehrman’s spiritual journey.

Ehrman responded first with the words, “Dale and I used to be friends”! He asked Martin why he thought it was appropriate to bring up Ehrman’s personal spiritual journey. Martin simply replied, “You made it public. You put it in your books.” Indeed, Martin pointed out the fact that Ehrman chose to make his own spiritual journey the first chapter in two of his popular books, and thus set the tone for the whole of each book with his opening gambit. Ehrman’s spiritual journey was in print, in the very same books where he makes his most radical pontifications.

Thus, again we find that his emotions drive his scholarship. Furthermore:

Wallace then began addressing their disagreements, but he did so in a surprising way: he put up extensive quotations from Ehrman’s own writings and showed that what Ehrman said to professional colleagues was quite different than what he said to laypersons. In other words, Wallace showed that Ehrman disagreed with Ehrman!

The implication was clear: Ehrman is too certain in scholarly circles and too skeptical in popular circles. He presents himself as an extreme modernist in one place and an extreme postmodernist in the other.

Another window into his scholarship was his flatly fallacious response to Wallace:

Ehrman then critiqued Wallace’s lecture as simply a message meant to comfort Christians into not doubting their Bibles, even saying that Wallace had provided no evidence for his position. (This is a debater’s standard technique: instead of wrestling with the arguments that his opponent brings up, he simply says that the opponent never said anything worth saying. But in this instance, I can only conclude that Ehrman was blowing smoke.)

One issue that seems to have come up repeatedly is Ehrman’s argument that:

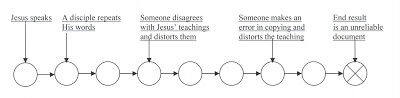

we don’t have “the copies of the copies of the copies of the copies of the copies of the copies of the originals.” (I counted six generations of copies before we get to our current manuscripts. Though I doubt that Ehrman was intentional in his repetition, this provides a taste of his rhetorical strategy.)….

[Wallace] noted, for example, that Ehrman had listed six generations of copies before we get any manuscripts, which is more than Ehrman implies in any of his printed work. Wallace then commented, “I suppose if a story is worth telling, it’s worth embellishing!”….

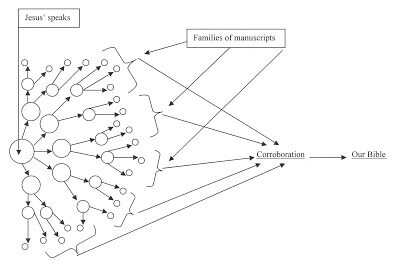

Ehrman’s oft-repeated line that we don’t even have copies of copies of copies was challenged by Wallace. He said that such rhetoric comes dangerously close to saying that New Testament copying was like the telephone game. He then proceeded to show six ways in which the telephone game is not at all like New Testament copying practices. I think it’s fair to say that this evidence alone should have retired Ehrman’s non-nuanced quip, but Ehrman continued saying it for the duration of the conference!

Just as Bart Ehrman fins the reading that he liked and then find the evidence to support it people who argue against the reliability of oral traditions find the evidence to support it by appealing to childish games such as telephone the point of which is to fail—that is what makes it fun.

Jesus did not just speak to one person who repeated it to one person, etc. Sometimes He spoke to one person, sometimes to a small group and sometimes thousands. Neither did one person write the New Testament. The New Testament is twenty-seven books written by some eight people (seven Jews, one Greek Doctor) and it draws from the accounts of many eyewitnesses.

Dr. Craig Blomberg, whilst being interviewed by Lee Strobel, explains why the game of telephone is not a good analogy for how oral traditions are passed on:

“When you’re carefully memorizing something and taking care not to pass it along until you’re sure you’ve got it right, you’re doing something very different from playing the game of telephone. In telephone half the fun is that the person may not have got it right or even heard it right the first time, and they cannot ask the person to repeat it.

Then you immediately pass it along, also in whispered tones that make it more likely the next person will goof something up even more. So yes, by the time it has circulated through a room of thirty people, the results can be hilarious.” “Then why,” I asked, “Isn’t that a good analogy for passing along ancient oral traditions?”…“If you really want to develop that analogy in light of the checks and balances of the first-century community, you’d have to say that every third person, out loud in a very clear voice, would have to ask the first person; ‘Do I still have it right?’ and change it if he didn’t. The community would constantly be monitoring what was said and intervening to make corrections along the way. That would preserve the integrity of the message,” he said. “And the result would be very different from that of the childish game of telephone.”1

Thus, the presupposition is not only that those people were ignorant and illiterate but not even smart enough to figure out how to reliably pass on information. And these were people who, sans written record keeping, carried around in the heads vast amounts of information. This was the era of memorizing entire genealogies, the scriptures, etc.

Foregoing a long elucidation; note that with relation to Matthew 24:36 Ehrman claims purposeful corruption. When he was asked why the conspirators had done such a poor job—since the assertion is that they removed the words “nor the Son” but left “alone” with reference to the Father’s knowledge—:

Ehrman’s argument that this passage is clearly an orthodox corruption either shows that the scribes were rather inept since they didn’t cover up the Father’s exclusive knowledge or else they changed their mood once they got into the corruption and had second guesses about deleting the “alone.” He [Wallace] concluded by saying that too often Ehrman’s views were only possible, but that Ehrman had turned possibility into probability and, at times, probability into certainty.

Do you see how this works, for Bart Ehrman? He can simply imagine entire scenarios, motivations, regrets, etc. out of pure thin air.

Further Ehrmanian conspiracy theories come in the form that of fact that:

Ehrman [supposes] an early, controlled text in which the earlier manuscripts were destroyed. Wallace noted that, You can’t have wild copying by untrained scribes and a proto-orthodox conspiracy simultaneously producing the same variants. Conspiracy implies control and wild copying is anything but controlled.” As far as I was concerned, this was the silver bullet that ripped a hole through Ehrman’s entire thesis.” Further, Wallace noted, the lack of controls that Ehrman argued for were only true of the Western text-type, not the Alexandrian.

We will begin the next segment with a consideration of a favored textual variant of Ehrman’s.