During his debate with Dr. John Lennox, Professor Richard Dawkins made an interesting remark about the Bible’s statements on the universe’s origins (hear the debate here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3).

The remark was actually not so much about the how of the universe’s origins but about the fact that the Bible stated millennia ago that the universe had a beginning, a fact that we moderns have proved mere decades ago.

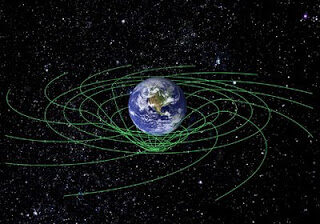

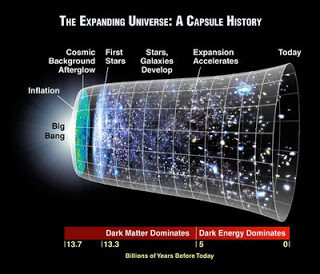

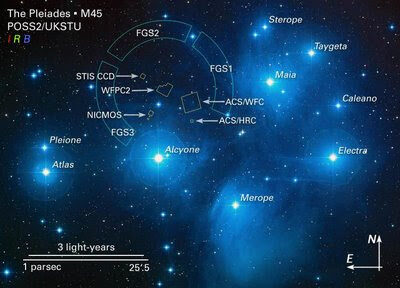

Prof. Richard Dawkins is not particularly impressed by this since the options were that the universe either had a beginning or is eternal. Therefore, he stated that the Bible had a 50/50% chance of getting it right (at which point the audience roared in approval).It is interesting to note that if the Bible is thought to be wrong on some point then that discredits the Bible. Yet, if the Bible is correct on some point then that does not accredit it. When the Bible is thought to be wrong it is all the more reason to discard it. But when it is right then it just got lucky. Clearly, this is a convenient argument whereby the Bible is useless since if it is wrong it is just wrong and if right then it is lucky.Let us consider some more biblical statements about cosmology and or astronomy:The earth hangs on nothing (Job 26:7).The earth is circular (Isaiah 40:22).The universe expands (Job 9:8; Psalm 104:2; Isaiah 40:22; 42:5; 42:44; 45:12; 51:13; Jeremiah 10:12; 51:15; Zechariah 12:1).The Pleiadian star system is bound together by mutual gravitational attraction (Job 38:31).

The Orion system has a belt (Job 38:31).

The universe consists of time, space, and matter (Genesis 1:1).Et al.Let us take an educated guess as to how Prof. Richard Dawkins would respond to each statement:

The earth hangs on nothing

Well, the earth either hangs on nothing or sits atop of something so the Bible had a 50/50% chance of getting it right.

The earth is circular

Well, the earth is either circular or some other shape and while the Bible had a less than a 50/50% chance of getting it right it just got lucky.

The universe expands

Well, the universe either expands, contracts, or is static and so the Bible had a 1 in 3 chance of getting it right.

The Pleiadian star system is bound together by mutual gravitational attraction

Well, the Pleiadian star system are either bound together by mutual gravitational attraction or not and so the Bible had a 50/50% chance of getting it right.

The Orion system has a belt

Well, the Orion system either has a belt or it does not and so the Bible had a 50/50% chance of getting it right.

The universe consists of time, space, and matter

Well, either the universe consists of time, space, and matter or it does not and so the Bible had a 50/50% chance of getting it right.

Clearly, these are not arguments but convenient quips.

Is it any wonder why the co-discoverer of the microwave background radiation and 1978 Nobel Prize recipient in physics, Arno Penzias, wrote:

The best data we have (concerning the big bang) are exactly what I would have predicted, had I nothing to go on but the five books of Moses, the Psalms, the Bible as a whole.1

Is it any wonder why Robert Jastrow, who was an agnostic, an astronomer, founder of NASA’s Goddard Institute of Space Studies, and who holds Edwin Hubbles’ former position at the Mount Wilson observatory, wrote:

…the astronomical evidence leads to a biblical view of the origin of the world. The details differ, but the essential elements in the astronomical and biblical accounts of Genesis are the same: the chain of events leading to man commenced suddenly and sharply at a definite moment in time, in a flash of light and energy. Some scientists are unhappy with the idea that the world began in this way. Until recently many of my colleagues preferred the Steady State theory, which holds that the Universe had no beginning and is eternal. But the latest evidence makes is almost certain that the Big Bang really did occur.2

Whether the issue is the Bible’s references to the above or to the hydrological cycle, the ocean currents, that the universe functions under the rule of laws, that time is not cyclical but linear the answer is just as simply: it just got lucky.

Prof. Richard Dawkins appears to be a pseudo-skeptic in that he is not honestly skeptical in seeking out information that may challenge or change his worldview. Rather, his interest appears to be to deny anything that conflicts with his worldview. Perhaps he does not have a worldview, but his worldview has him.

- 1. The New York Times, March 12, 1978

- 2. Robert Jastrow, God and the Astronomers (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1978), p. 14 He also wrote:

“Theologians generally are delighted with the proof that the Universe had a beginning, but astronomers are curiously upset. Their reactions provide an interesting demonstration of the response of the scientific mind-supposedly a very objective mind-when evidence uncovered by science itself leads to a conflict with the articles of faith in our profession. It turns out that the scientist behaves the way the rest of us do when our beliefs are in conflict with the evidence. We become irritated, we pretend the conflict does not exist, or we paper it over with meaningless phrases.” (ibid. p. 16)

Also:

“For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.” (ibid. p. 116)He moreover wrote:

“…some prominent scientists began to feel the same irritation over the expanding Universe that Einstein had expressed earlier. Eddington [English astronomer Arthur Eddington] wrote in 1931, ‘I have no axe to grind in this discussion,’ but ‘the notion of a beginning is repugnant to me…I simply do not believe that the present order of things started off with a bang…the expanding Universe is preposterous…incredible…it leaves me cold.’ The German chemist, Walter Nernst, wrote, ‘To deny the infinite duration of time would be to betray the very foundation of science.’ More recently, Phillip Morrison of MIT said in a BBC film on cosmology, ‘I find it hard to accept the Big Bang theory; I would like to reject it.’ And Allan Sandage of Palomar Observatory, who established the uniformity of the expansion of the Universe out to nearly ten billion light years, said, ‘It is such a strange conclusion…it cannot really be true‘…Einstein wrote, ‘The scientist is possessed by the sense of universal causation.’ This religious faith of the scientist is violated by the discovery that the world had a beginning under conditions in which the known laws of physics are not valid, and as a product of forces or circumstances we cannot discover. When that happens, the scientist has lost control. If he really examined the implications, he would be traumatized.” (ibid. pp. 112-114, italics in original)